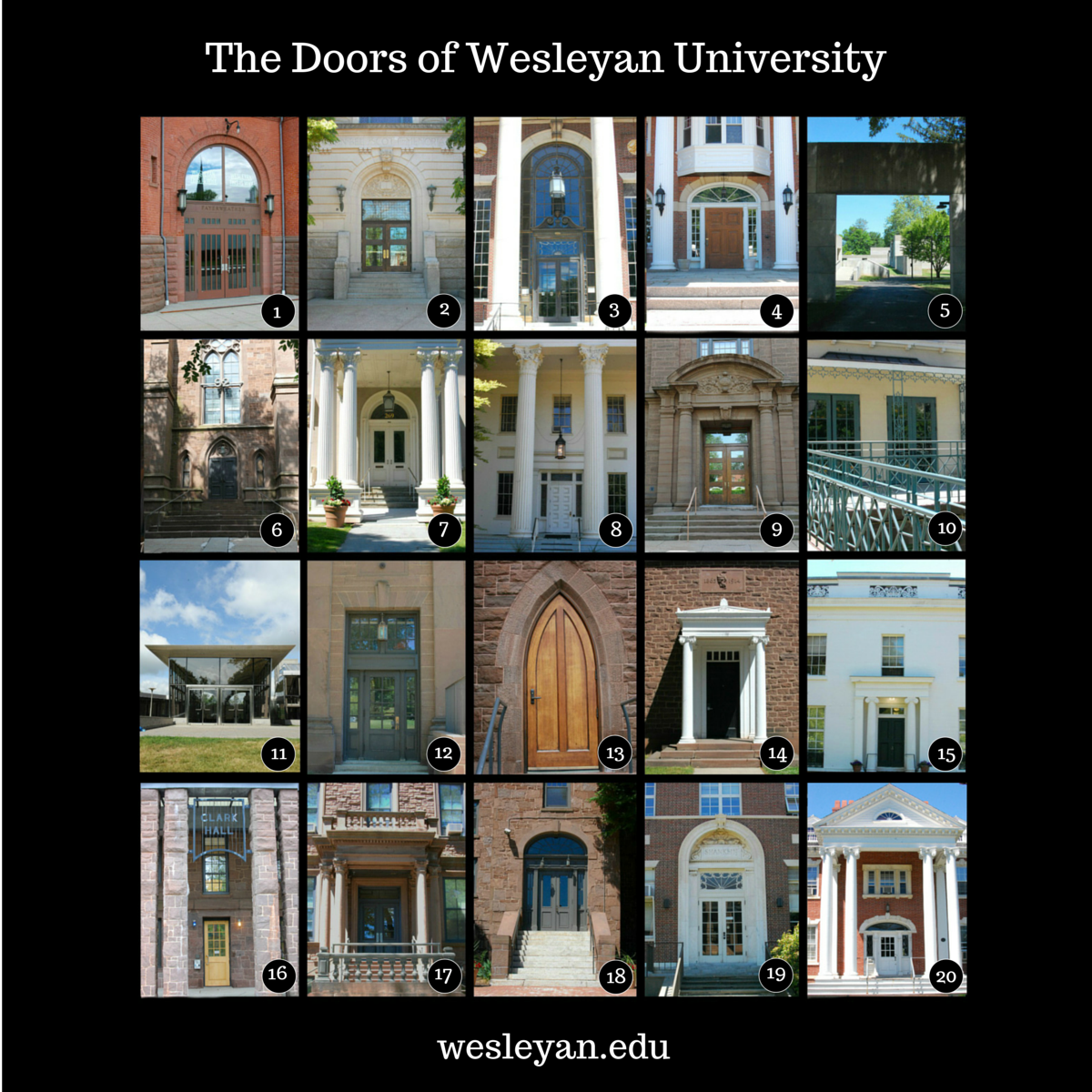

![The doors of Wesleyan. (1)]() Students walk past them and through them during their years on campus. So how well do you know these iconic Wesleyan building entryways? Quiz yourself. The answers are below. For more information on the buildings, download the Wesleyan University Walking Tour (on which this text is based) or type m.wesleyan.edu/walkingtour into your mobile device’s browser to take a virtual walking tour!

Students walk past them and through them during their years on campus. So how well do you know these iconic Wesleyan building entryways? Quiz yourself. The answers are below. For more information on the buildings, download the Wesleyan University Walking Tour (on which this text is based) or type m.wesleyan.edu/walkingtour into your mobile device’s browser to take a virtual walking tour!

![Fayerweather]()

Fayerweather

1. Fayerweather/Beckham Hall – 55 Wyllys Avenue

Built in 1894, Fayerweather originally served as the university’s gymnasium. The building, with its distinctive Romanesque towers, was designed by architect J. C. Cady, who also designed the south wing of New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, as well as buildings at Williams College and Yale University.

![Allbritton]()

Allbritton Center

2. Allbritton Center – 222 Church Street

The Allbritton Center is housed in a classic Beaux Arts building designed by Charles Alonzo Rich. Completed in 1904, the building was originally a physics facility dedicated to John Scott Bell, Class of 1881. Scott Lab, as it was known, was remodeled and opened in 1984 as the Davenport Student Center, dedicated to Edith Jefferson Andrus Davenport, Class of 1897. The building was renovated again in 2007, and named for Robert Allbritton ’92.

![Olin Library]()

Olin Library

3. Olin Library – 252 Church Street

The grand Georgian-style Olin Library was dedicated in 1928 to memorialize Wesleyan’s second president, Stephen Olin, and his son, Stephen H. Olin, Class of 1866, a university trustee, who was born in the President’s House on campus. Henry Bacon sketched the design of the building, and the architects were McKim, Mead & White. A 1939 addition almost doubled the size of the book stacks. In 1986, 46,000 square feet were added, allowing for the incorporation of floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Andrus Field.

![Alpha Delta Phi]()

Alpha Delta Phi

4. Alpha Delta Phi – 185 High Street

The colonial-style Alpha Delta Phi building, designed by Charles Alonzo Rich, was completed in 1906. A large addition was built onto the back of the house in 1925, and a new front entrance was constructed in 2005. Alpha Delta Phi, a self-governing coeducational literary society, has been offering open lectures, poetry readings, plays, and musical events since 1884, when the chapter’s first house was built on the current lot.

![18424455331_b9dccdf5f2_k]()

Center for the Arts

5. Center for the Arts – Washington Terrace

The Center for the Arts (CFA) opened in fall 1973, dedicated to studio arts, art history, film, music, theater, and dance. Made from Indiana limestone and designed by Kevin Roche of Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo and Associates, the 11-building complex was situated to preserve the existing trees on the site and designed with underground spaces to minimize scale above ground. The complex includes studios, a graphics workshop, the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery, Crowell Concert Hall, CFA Theater, CFA Hall, World Music Hall, and Rehearsal Hall. Click here to view upcoming CFA events.

![Patricelli '92 Theater (photo by Jack Gorlin)]()

Patricelli ’92 Theater

6. Patricelli ’92 Theater – 213 High Street

Completed in 1868 as Rich Hall, Patricelli ’92 Theater originally served as the university library. When Olin Library opened in 1928, the building was converted into a theater with a gift from the class of 1892. In 2003, the building reopened with a renovated interior and was dedicated to Leonard J. Patricelli ’29, with a gift from Robert Patricelli ’61. The theater houses Second Stage, one of the oldest student-run theater organizations in the United States, founded by Jan Eliasberg ’74.

![President's House]()

President’s House

7. President’s House – 269 High Street

The President’s House is an Italianate residence built in 1834 that was once the home of the widow of Samuel Dickinson Hubbard, postmaster general from 1852–53. The structure began serving as the President’s House in 1904 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

![russell house]()

Russell House

8. Russell House – 350 High Street

New Haven architect Ithiel Town designed Russell House, a stately Greek revival building that was completed in 1830 as a home for Samuel Russell, a China trading merchant, and his wife. Wesleyan received the building as a gift in 1937 and it served as the Honors College until 1996. The building was named a National Historical Landmark in 2001. Today Russell House serves as a venue for musical programs, literary readings, and lectures, including the Russell House Prose and Poetry series and Music at the Russell House series. It also houses the Philosophy Department.

![Fisk Hall]()

Fisk Hall

9. Fisk Hall – 262 High Street

Fisk Hall, named in honor of Willbur Fisk, Wesleyan’s first president, was completed in 1904. Designed in the Romanesque style by Cady, Berg & See of New York City, it is made of Portland (Conn.) brownstone.

![Downey House]()

Downey House

10. Downey House – 294 High Street

Built in 1842 as the residence of Elihu W.N. Starr and housing the Misses Patten’s School for girls from 1889–1911, Downey House, named for Dr. David G. Downey, Class of 1884, was acquired by Wesleyan in 1922. The building served as a faculty club from 1923 to 1935. In 1936, it became a campus social center, with a campus store, post office, and dining room. It also housed The Cardinal Pub in the late 1970s. Today, Downey House houses the offices of the English, Classical Studies, and Romance Languages and Literature departments.

![Zelnick Pavilion]()

Zelnick Pavilion

11. Zelnick Pavillion – 217 High Street

The glass-and-steel Zelnick Pavilion, adjoined to Memorial Chapel, was dedicated in 2003 to honor the Zelnick family. The pavilion provides a reception space for the chapel and Patricelli ’92 Theater, as well as an indoor connection between the two spaces.

![North College]()

North College

12. North College – 237 High Street

South College and the original North College were constructed in 1825 by the city of Middletown to house Captain Partridge’s American Literary, Scientific, and Military Academy. Called the Dormitory until fall 1871, North College originally accommodated about 100 students. The old North College building was destroyed by fire in 1906. The new North College opened in 1907 as a reproduction of the original building. Administrative offices began moving in to the building in the 1950s.

![Memorial Chapel]()

Memorial Chapel

13. Memorial Chapel – 221 High Street

The nondenominational Memorial Chapel was built in 1871 to honor alumni and students who died in the Civil War. Classrooms were on the first floor, with the chapel on the second floor. In 1916, architect Henry Bacon remodeled the building into the two-story space it remains today. The chapel underwent a major renovation in 2003, dedicated to the memory of Edward Ernest Matthews, Class of 1889, by his stepdaughter. The building hosts religious services, large lectures and concerts, and weddings. It also has a 3,000-pipe Holtkamp organ and a meditation room.

![Skull and Serpent]()

Skull and Serpent

14. Skull and Serpent – 16 Wyllys Avenue

Affectionately known as “The Tomb,” the Skull and Serpent Society building was designed by Henry Bacon 1914. Founded in 1865, the secret society was the university’s oldest senior honorary organization.

![University Relations]()

University Relations

15. University Relations – 318 High Street

Built in the Greek Revival style and completed in 1842 on a portion of the Russell family estate as a home for Edward A. Russell, a foreign textile merchant and brother to Samuel Russell, the building was sold to Wesleyan in the early 1930s and used as a fraternity house for Sigma Nu and, later, Kappa Nu Kappa, before being remodeled for use by University Relations. While no one is certain, the architect of the house is thought to be either A. J. Davis or Ithiel Town.

![door clark hall]()

Clark Hall

16. Clark Hall – 268 Church Street

Clark Hall, a 1916 brownstone building designed as a dormitory by Henry Bacon, is named for Judge John C. Clark, Class of 1886. In 2002, Clark underwent a complete renovation to accommodate 135 first-year students in one-room doubles.

![Judd Hall]()

Judd Hall

17. Judd Hall – 207 High Street

Judd Hall, an Empire-style brownstone building designed by Bryant and Rogers, was one of the first buildings in the country devoted exclusively to undergraduate science instruction. It first opened in 1871 and was named for Orange Judd, Class of 1847, a Wesleyan trustee and generous donor who supported coeducation. For a period of time, all of the building’s doors were painted orange, in homage to Judd. Today it is home to the Psychology Department.

![South College]()

South College

18. South College – 229 High Street

South College is the oldest building on campus. Originally called the Lyceum or the Chapel, it served as home to classrooms, an early library collection, and a chapel. In 1906, it was remodeled to contain offices and a raised entrance was built. A cupola and belfry, designed by Henry Bacon, were added in 1916. Today South College houses the President’s Office, the Office of University Communications, and the 24-bell Wesleyan Carillon.

![Shanklin Laboratory]()

Shanklin Laboratory

19. Shanklin Laboratory – 237 Church Street

Shanklin Laboratory was completed in 1928 and named for former Wesleyan University president William Arnold Shanklin. The building underwent major renovations from the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s.

![Center for African American Studies]()

Center for African American Studies

20. Center for African American Studies/Malcolm X House

– 343 High Street

The Center for African American Studies and Malcolm X House are both contained in a 1901 two-building complex built by Thomas MacDonough Russell and acquired by Wesleyan in 1934. After being damaged by fire in 1967, the building was renovated in 1969, and its residential section was renamed the Malcolm X House.

Photos by Olivia Drake and Laurie Kenney. Patricelli ’92 Theater photo by Jack Gorlin ’16.